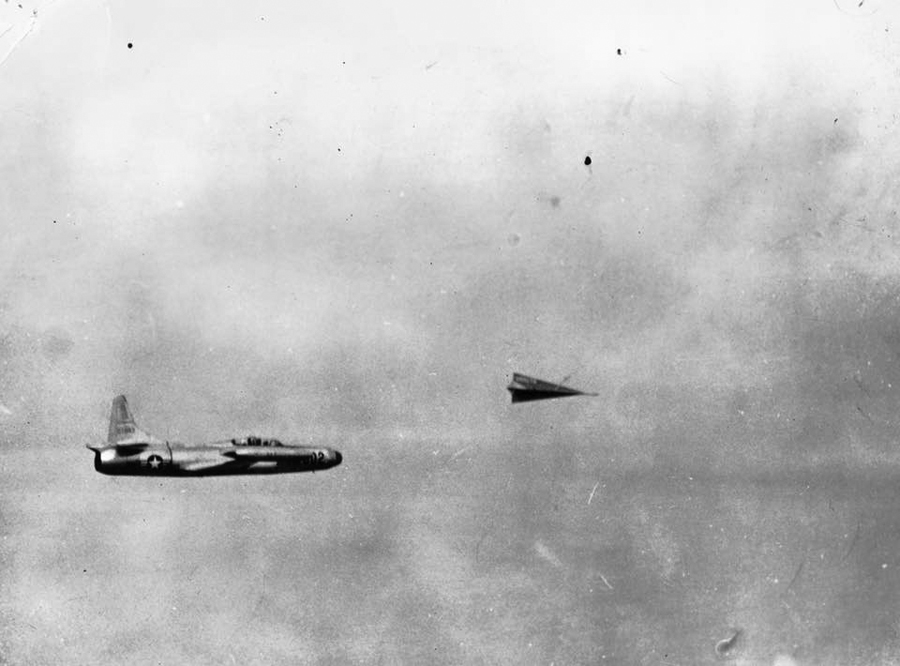

June 3, 1949: The XF-90 made its first flight, flown by Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier. The XF-90 was built in response to a U.S. Air Force requirement for a long-range penetration fighter and bomber escort. The same requirement produced the McDonnell XF-88 Voodoo. Lockheed received a contract for two prototype XP-90s (redesignated XF-90 in 1948).

The design was developed by Willis Hawkins and the Skunk Works team under Kelly Johnson. Two prototypes were built. Embodying the experience gained in developing the P-80 Shooting Star, the XF-90 shared some design traits with the older Lockheed fighter, albeit with swept-wings; however, this latter design choice could not sufficiently make up for the project’s underpowered engines, and the XF-90 never entered production.

The XF-90 was the first Air Force jet with an afterburner and the first Lockheed jet to fly supersonic, albeit in a dive. It also incorporated an unusual vertical stabilizer that could be moved fore and aft for horizontal stabilizer adjustment. Partly because Lockheed’s design proved underpowered, it placed second to McDonnell’s XF-88 Voodoo which won the production contract in September 1950, before the penetration fighter project was abandoned altogether.

Upon Lockheed losing the production contract, the two prototypes were retired to other testing roles. The first aircraft was shipped to the NACA Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1953 for structural tests. It was no longer flyable, and its extremely strong airframe was tested to destruction. The other survived three atomic blasts at Frenchman Flat within the Nevada Test Site in 1952.

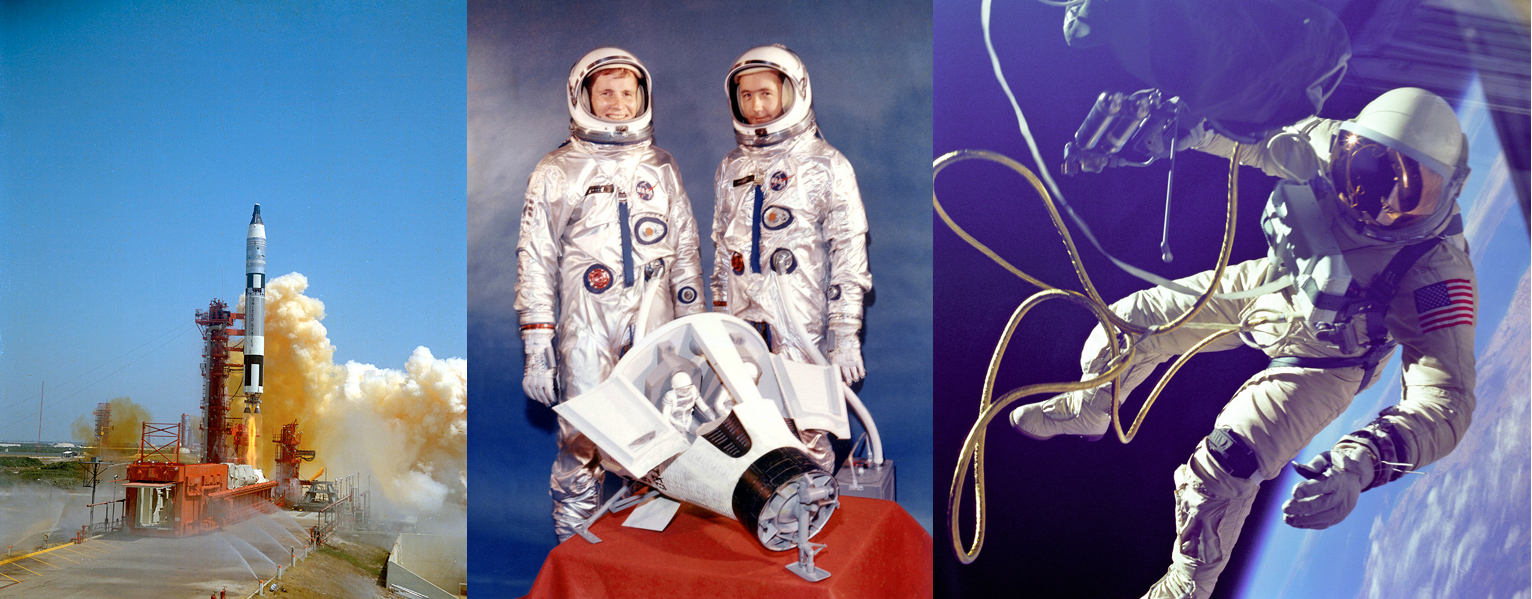

June 3, 1965: Gemini IV launched from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station in Florida, with astronauts James McDivitt and Edward White on board. This was the second crewed spaceflight in NASA’s Project Gemini. It was the 10th crewed American spaceflight. McDivitt and White circled the Earth six times in four days.

The highlight of the mission was the first space walk by an American, during which White floated free outside the spacecraft, tethered to it, for approximately 20 minutes. The flight also included the first attempt to make a space rendezvous as McDivitt attempted to maneuver his craft close to the Titan II upper stage which launched it into orbit, but this was not successful.

The flight was the first American flight to perform many scientific experiments in space, including use of a sextant to investigate the use of celestial navigation for lunar flight in the Apollo program.

June 3, 1969: A test team flew the first sortie in a series to certify the F-4E Phantom II with a Target Identification System, Electro-Optical system for Tactical Air Command. Beginning in 1973, Phantom II aircraft possessed target-identification systems for long-range visual identification of both airborne and ground targets.

Each system acted like a television camera with a zoom lens to aid in positive identification, and a system called Pave Tack, which provided day and night all-weather capability to acquire, track and designate ground targets for laser, infrared, and electro-optically guided weapons.

The final 10 production Phantom II Aircraft introduced a Northrop AN/ASX-1 Target Identification System, Electro-Optical system attached to the left wing. The system identified aircraft out of range of the pilot’s naked eye. This equipment contained two distinct zoom settings that were linked to the aircraft’s radar scope.

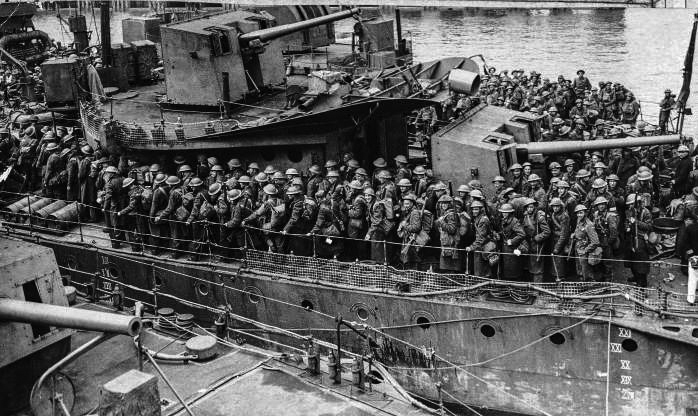

June 4, 1940: The Allied forces’ evacuation of soldiers from Dunkirk, France, to England was declared complete on the day. The operation that started on May 26 successfully saved more than 338,000 men. Code-named Operation Dynamo, the rescue mission famously used every seaworthy vessel available, military and civilian, including fishing boats, private yachts and lifeboats.

June 4, 1954: At Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., Maj. Arthur W. “Kit” Murray flew the experimental Bell X-1A research rocketplane to an altitude of 89,810 feet at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He flew high enough that the sky darkened, and he was able to see the curvature of the Earth. Newspapers called him “America’s first space pilot.” The X-1A reached Mach 1.97. Encountering the same inertial coupling instability as had Chuck Yeager on Nov. 20, 1953, though at a lower speed, the X-1A tumbled out of control.

The rocket plane lost more than 20,000 feet of altitude before Murray could regain control. For this accomplishment, Murray was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. One week earlier on May 28, 1954, Murray had flown the X-1A to an unofficial world record altitude of 90,440 feet. The Bell X-1A was a follow-on project to the earlier X-1. It was designed and built by the Bell Aircraft Corporation in Buffalo, N.Y., to investigate speeds above Mach 2 and altitudes above 90,000 feet. It was carried to altitude by a modified Boeing B-29 Superfortress then dropped for the research flight. The X-1A was destroyed by an internal explosion July 20, 1955.

June 4, 1969: Lockheed’s C-5A Galaxy Number Two, the world’s largest transport aircraft, arrived at the Air Force Flight Test Center, Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., for joint Air Force-contractor Category I and II testing.

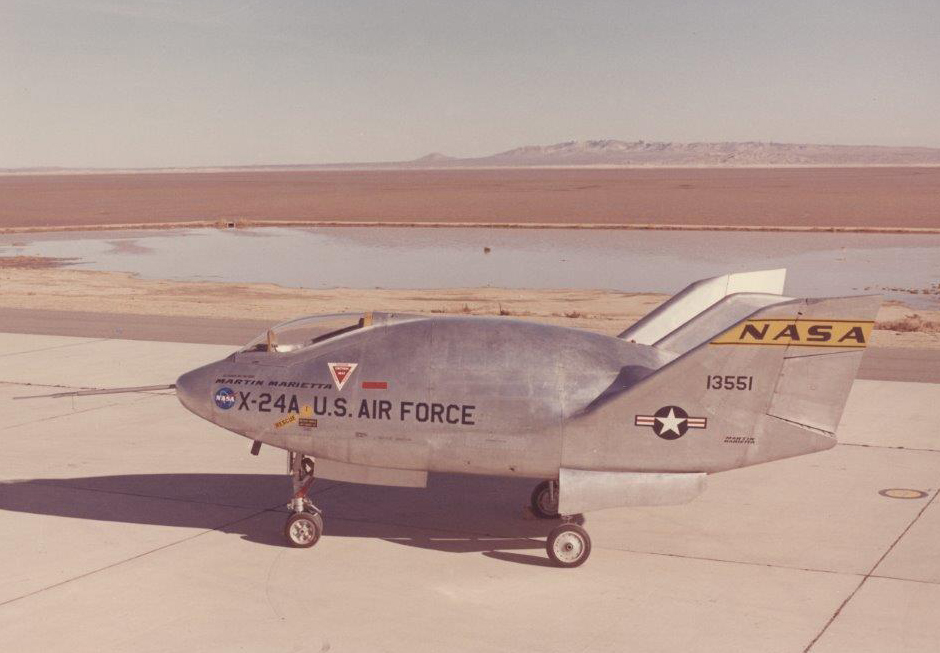

June 4, 1971: The Martin Marietta X-24A prototype aircraft made its last flight on this day. After 28 flights, Air Force engineers redesigned and heavily modified the blunt-shaped X‑24A and renamed it the X-24B. The “B” model possessed a longer fuselage, increased width, and sharply changed platform. The X-24B proved to have three times the maneuverability of the original design. Both, the United States Air Force NASA jointly developed the aircraft within a program named PILOT.

This program ran from 1963 through 1975. The program’s primary purpose involved testing of lifting body concepts, experimenting with the concept of unpowered reentry and landing. The Space Shuttle later utilized these same concepts. During testing, the X-24 would detach from a modified B-52 Stratofortress at high altitudes before igniting its rocket engine and after expending its fuel load, the pilot would glide the X-24 to an unpowered landing.

June 4, 1974: The first female to be designated a U.S. Army Aviator, 2nd Lt. Sally D. Woolfolk graduated from the Rotary Wing Flight School at the Army Aviation School, Fort Rucker, Ala. She was the first woman to be designated a U.S. Army Aviator. Woolfolk joined the U.S. Army in January 1973. After attending an 11-week officer’s candidate course at Fort McClellan, Ala., she was commissioned a second lieutenant. Woolfolk was then assigned to a military intelligence course at Fort Huachuca, near Sierra Vista, Arizona, close to the U.S.-Mexico border. At the suggestion of another student in the intelligence course, Woolfolk applied for helicopter flight training. She was the only woman in her class at Fort Rucker.

June 4, 1983: After 25 years of service, the Republic F-105 Thunderchief supersonic fighter-bomber was withdrawn from service. The last U.S. Air Force unit flying the F-105, the 419th Tactical Fighter Wing at Hill AFB, Utah, flew a Diamond of Diamonds 24-ship formation to mark the occasion. The F-15 was being replaced by the General Dynamics F-16 Falcon. Of 833 Thunderchiefs built by Republic Aviation Corporation, 334 were lost to enemy action during the Vietnam War. Though designed for air-to-ground attack missions, F-105s are officially credited with 27.5 victories in air combat.

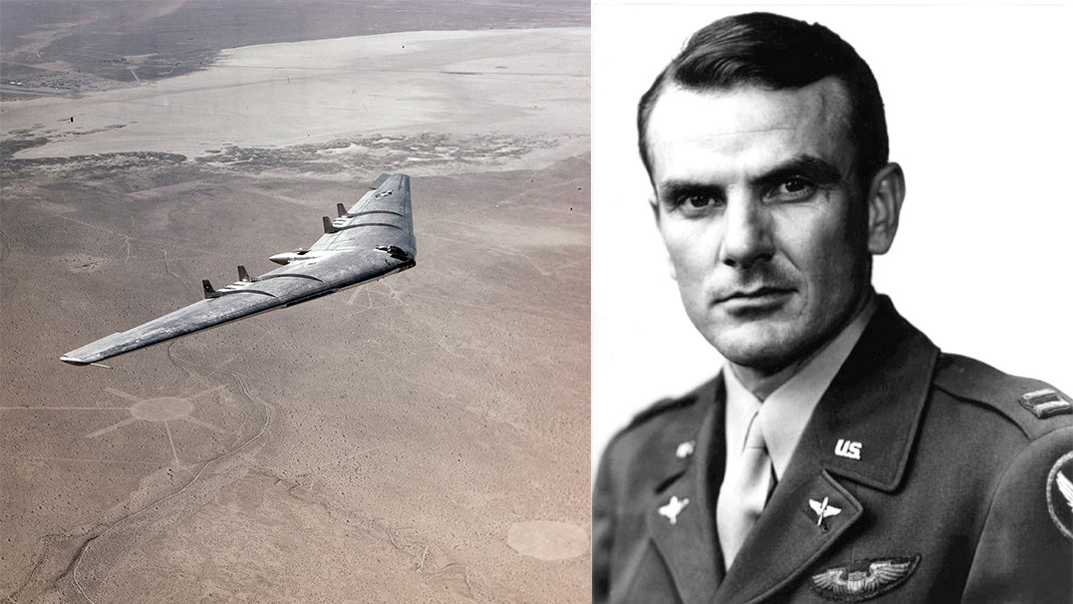

June 5, 1948: The second Northrop YB-49 “Flying Wing” was undergoing stall recovery performance testing at 40,000 feet, north of Muroc Army Air Field (now Edwards AFB, Calif.). On board was the pilot, Maj. Daniel A. Forbes Jr., co-pilot Capt. Glen W. Edwards, flight engineer 1st Lt. Edward L. Swindell, and civilian engineers Charles H. LaFountain and Clare C. Lesser. The aircraft suffered a catastrophic structural failure with the outer wing panels tearing off, and the aircraft crashed approximately 10 miles (16 kilometers) east of the small desert town of Mojave.

The entire crew was killed. The YB-49 was an experimental jet engine-powered bomber, modified from a propeller-driven Northrop XB-35. It was hoped that the all-wing design would result in a highly efficient airplane because of its very low drag characteristics. However, the design could be unstable under various flight conditions,

A few months after the crash, the first YB-49 was destroyed in a taxiing accident and the project cancelled. It would be 41 years before the concept would be successful with the Northrop B-2 Spirit. The YB-49 was a very unusual configuration for an aircraft of that time: There was no fuselage or tail control surfaces, and the crew compartment, engines, fuel, landing gear and armament was contained within the wing. Air intakes for the turbojet engines were placed in the leading edge of the wing. The exhaust nozzles were at the trailing edge. Four small vertical fins for improved yaw stability were also at the trailing edge. Only the two Northrop YB-49s were built and tested by Northrop and the U.S. Air Force for nearly two years. Although an additional nine YB-35s were ordered converted, the B-49 did not go into production.

Glen Walter Edwards was born at Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada, March 5, 1916, the second son of Claude Gustin Edwards, a real estate salesman, and Mary Elizabeth Briggeman Edwards. The family immigrated to the United States in August 1923 and settled near Lincoln, Calif. He attended Lincoln High School, where he was a member of the Spanish Club and worked on the school newspaper, “El Eco.” He graduated in 1936.

Edwards attended Placer Junior College, Auburn, Calif., before transferring to the University of California, Berkeley. He graduated in 1941 with a Bachelor of Arts degree, and then enlisted in the U.S. Army as an aviation cadet on July 16, 1941.

Following pilot training, Edwards was commissioned as a second lieutenant on Feb. 6, 1942. He was promoted to first lieutenant on Sept. 16, 1942. Edwards flew 50 combat missions in the Douglas A-20 Havoc light bomber with the 86th Bombardment Squadron (Light), 47th Bomb Group, in North Africa and fought at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass, Feb. 19-24, 1943. He was promoted to captain April 28, 1943. He also flew during the invasion of Sicily, in late 1943.

Edwards returned to the United States and was assigned to the Pilot Standardization Board but was then sent to train as a test pilot at Wright Field. Edwards was assigned as a test pilot in 1944 and tested the Northrop XB-35 and Convair XB-36. After World War II came to an end the U.S. Army and Air Corps were demobilized to 1/16 of their peak levels (from 8,200,000 to 554,000). Edwards was retained but reverted to the rank of first lieutenant. He had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters (four awards). He was transferred to the U.S. Air Force after it was established as a separate service.

Edwards was recommended to fly the Bell X-1 rocket plane, but when that assignment went to Chuck Yeager, Edwards was sent to Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., to study aeronautical engineering. He earned a masters’ degree in engineering in 1947.

Following the crash of the YB-49, Topeka Air Force Base in Kansas was renamed Forbes Air Force Base, and Muroc Air Force Base was renamed Edwards Air Force Base in honor of Edwards.

Edwards is buried at the Lincoln Cemetery, Lincoln, Calif.

June 5, 1961: The first class of the Aerospace Research Pilot School began on this day. The class consisted of four permanent members of the Test Pilot School and one from the Air Force Flight Test Centerís Directorate of Flight Test. The initial class offered the instructors’ valuable teaching experience as the Aerospace Research Pilot Course transitioned to the task of training aerospace research pilots.

Inspired by the Royal Air Force’s Empire Test Pilots’ School, Col. Ernest K. Warburton, chief of the Flight Test Section at Wright Field, Ohio, set about changing the role and status of flight testing in the U.S. Army Air Forces. His goals for the flight test community included standardization and independence, which became realized with the establishment of the Air Technical Command Flight Test Training unit on Sept. 9, 1944, and the independent Flight Test Division in 1945.

The AAF possessed a formal program of study to train young pilots to become flight test professionals. Shortly after the first class graduated, officials changed the name of the school to the Flight Section School Branch incorporating an increased focus on academic theory. In 1945, the school moved to Vandalia, Ohio, James M. Cox Dayton International Airport. The school once again changed its name to the Flight Performance School and fell under the responsibility of Lt. Col. John R. Muehlberg, the first official school commandant. On Feb. 4, 1951, the school transferred to Edwards Air Force Base. The enormous dry lakebed, extremely long runways, and clear weather served the U.S. Air Force and the school well, as aircraft performance continued to increase.

The schoolhouse took residence in an old weather-beaten wooden hangar along the flight line of what became known as South Base. Although the quarters were spartan, the weather was superb with only two flying days lost due to weather in the first seven months of operation. Taking advantage of the calm morning air, students started the day flying missions to collect test data. Afternoons were spent in the lecture hall, and evenings were devoted to reducing data from the day’s flights. Once reduced, the data was woven into a report that summarized the test and the student’s conclusions. Student enrollment issues improved in 1953, when the school was moved out of Air Research and Development Command, thus allowing for the selection boards to draw from a much larger, Air Force-wide, pool of applicants, rather than just the local test squadrons.

June 5, 1981: A McDonnell Douglas KC-10 completed a rigorous 28-day air refueling qualification program at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. The qualification program was for Strategic Air Command.

June 6, 1944: A huge airborne armada, nine planes wide and 200 miles long, carries American British and Canadian troops across the British Channel for the D-Day invasion of Europe. The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as D-Day, it was the largest seaborne invasion in history.

The operation began the liberation of France (and later Western Europe) and laid the foundations of the Allied victory on the Western Front.

Planning for the operation began in 1943. In the months leading up to the invasion, the Allies conducted a substantial military deception, codenamed Operation Bodyguard, to mislead the Germans as to the date and location of the main Allied landings. The weather on D-Day was far from ideal, and the operation had to be delayed 24 hours; a further postponement would have meant a delay of at least two weeks, as the invasion planners had requirements for the phase of the moon, the tides, and the time of day that meant only a few days each month were deemed suitable. Adolf Hitler placed Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in command of German forces and of developing fortifications along the Atlantic Wall in anticipation of an Allied invasion. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed Maj. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower in command of Allied forces.

The amphibious landings were preceded by extensive aerial and naval bombardment and an airborne assault to the landing of 24,000 American, British, and Canadian airborne troops shortly after midnight. Allied infantry and armored divisions began landing on the coast of France at 6:30 a.m. The target 50-mile stretch of the Normandy coast was divided into five sectors: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. Strong winds blew the landing craft east of their intended positions, particularly at Utah and Omaha.

The men landed under heavy fire from gun emplacements overlooking the beaches, and the shore was mined and covered with obstacles such as wooden stakes, metal tripods, and barbed wire, making the work of the beach-clearing teams difficult and dangerous. Casualties were heaviest at Omaha, with its high cliffs. At Gold, Juno, and Sword, several fortified towns were cleared in house-to-house fighting, and two major gun emplacements at Gold were disabled using specialized tanks.

The Allies failed to achieve any of their goals on the first day. Carentan, Saint-LÙ, and Bayeux remained in German hands, and Caen, a major objective, was not captured until July 21. Only two of the beaches (Juno and Gold) were linked on the first day, and all five beachheads were not connected until June 12; however, the operation gained a foothold that the Allies gradually expanded over the coming months. German casualties on D-Day have been estimated at 4,000 to 9,000 men. Allied casualties were documented for at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead.

For more on D-Day, visit:

Meticulous planning led way to D-Day landings

Meticulous planning led way to D-Day landings

D-Day marked turning point in World War II

D-Day marked turning point in World War II

Five things you may not know about D-Day

Five things you may not know about D-Day

June 6, 1944: The Lockheed XP-58 Chain Lightning made its first flight, from the Lockheed facility at Burbank, Calif., (pictured) to Muroc Army Air Field (now Edwards AFB), with company test pilot Joe Towle at the controls. The aircraft was an upgraded version of the companyís legendary P-38 Lightning, designed for a variety of roles.

June 6, 1959: The first ground test of Thiokol’s XLR-99 liquid fuel rocket engine for the X-15 took place at the Static Test Stand at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Delivery 50,000 pounds of thrust at ground level, it was the most powerful and complex throttleable rocket propulsion system in the world.

June 6, 1966: The National Sonic Boom Test project began. This was a joint Air Force, NASA, and FAA study of jet noise and sonic boom effects on structures and people. Two dedicated houses were built and instrumented near Bldg. P-1, and a third in Lancaster to catch sonic spillover effects. Repeated supersonic passes by a variety of aircraft recorded data and the effects upon the buildings and some 100 test personnel. The objective of the program was to apply the data to supersonic transport (SST) development.

Shock waves develop simultaneously with supersonic flight in the atmosphere, and the passage of these shock waves over people, animals and structures on the ground cannot be eliminated. However, the real concern is for civil supersonic overland flight operations that cause repeated sonic booms over very large areas. The feasibility of routine civil supersonic flight operations and particularly their acceptance by the general public for overland routes may be largely a function of the severity of the sonic boom, but also encompasses a plethora of sociological as well as technological considerations.

A sonic boom does not occur only at the moment an object crosses the speed of sound, and neither is it heard in all directions emanating from the supersonic object. Rather the boom is a continuous effect that occurs while the object is travelling at supersonic speeds, but it affects only observers that are positioned at a point that intersects a region in the shape of a geometrical cone behind the object. As the object moves, this conical region also moves behind it and when the cone passes over the observer, they briefly experience the boom.

Douglas DC-4E (r/n NX 18100) in flight, written at the bottom of the image, “DC-4, 10-5-38 [October 5, 1938], 14001”.

Credit: unknown (Smithsonian Institution)

June 7, 1938: The Douglas DC-4E with test pilot Carl Cover at the controls, made its first flight from Clover Field in Santa Monica, Calif. The design originated in 1935 from a requirement by United Air Lines. The goal was to develop a much larger and more sophisticated replacement for the DC-3 before the first DC-3 had even flown. Such was the initial interest from other airlines, that American Airlines, Eastern Air Lines, Pan American Airways and Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) joined United, providing $100,000 each toward the cost of developing the new aircraft.

As cost and complexity rose, Pan American and TWA withdrew their funds in favor of the Boeing 307, which was anticipated to be less costly. With a planned day capacity of 42 passengers (13 rows of two or more seats and a central aisle) or 30 as a sleeper transport (like the DST), the DC-4 (as it was then known) would seat twice as many people as the DC-3 and would be the first large aircraft with a nosewheel. Other innovations included auxiliary power units, power-boosted flight controls, alternating current electrical system and air conditioning.

Cabin pressurization was also planned for production aircraft. The design was abandoned in favor of a marginally smaller, less-complex four-engine design, with a single vertical fin and 21 feet shorter wingspan. This newer design was also designated DC-4, leading the earlier design to be redesignated DC-4E (E for “experimental”). In late 1939, the DC-4E was sold to Imperial Japanese Airways, which was buying American aircraft for evaluation and technology transfer during this period; at the behest of the Imperial Japanese Navy, it was reverse-engineered, becoming the basis for the unsuccessful Nakajima G5N bomber. To conceal its transfer to the Nakajima Aircraft Company for study, the Japanese press reported shortly after purchase that the DC-4E had crashed in Tokyo Bay.

June 7, 1960: The supersonic tow target was flown on its first sortie, at subsonic speeds at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. The 16-foot missile-shaped device, built by Norair, was designed to be deployed from a tow aircraft and be flown at supersonic speeds at the end of a seven-and-a-half mile long stepped steel cable.

June 7, 1966: The Ryan XV-8A test vehicle arrived at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., for Test and Evaluation by the Army Aviation Test Activity. It was tested for suitability as a “flying Jeep.”

June 7, 1979: A C-141B, the stretched version of the Starlifter, arrived at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., for Category III (final evaluation) before release to the Military Airlift Command. Two fuselage plugs added 23-and-a-half feet to the cargo carrier’s length, and an aerial refueling receptacle was added to the upper surface of the fuselage. Ultimately, all of MAC’s C-141As would be modified into the new configuration.

June 7, 2002: A multi-role, remotely piloted unmanned aerial vehicle — the MQ-1 Predator — launched a mini-UAV while in flight over Edwards Air Force Base. This became the first time an operational UAV demonstrated the capability to carry and launch another such aerial vehicle.

The mini-UAV, a 57-pound Navy Flight Inserted Detector Expendable for Reconnaissance (FINDER) was carried on a wing pylon and released at an altitude of 10,000 feet. Following launch, it successfully conducted a 25-minute pre-programmed mission before a flight technician took control and landed it on the lakebed.

The MQ-1B Predator operates as an armed, multi-mission, medium-altitude, long-endurance remotely piloted aircraft that is employed primarily as an intelligence-collection asset and secondarily against dynamic execution targets. Given its ability to loiter in an area for a significant amount of time, wide-range sensors, multi-mode communications suite, and precision weapons, it provides a unique capability to perform strike, coordination and reconnaissance sorties against high-value, fleeting, and time-sensitive targets.

Predators can also perform the following missions and tasks: intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, close air support, combat search and rescue, precision strike, buddy-lase, convoy/raid overwatch, route clearance, target development, and terminal air guidance. The MQ-1’s capabilities make it uniquely qualified to conduct irregular warfare operations in support of combatant commander objectives.

June 8, 1959: At Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., North American Aviation’s Chief Engineering Test Pilot, A. Scott Crossfield, made the first flight of the X-15A hypersonic research rocketplane at Edwards AFB, Calif. The aircraft was the first of three X-15s built for the U.S. Air Force and NASA. It was airdropped from a Boeing NB-52A Stratofortress, 52-003, at 37,550 feet over Rosamond Dry Lake. This was an unpowered glide flight to check the flying characteristics and aircraft systems, so there were no propellants or oxidizers aboard, other than hydrogen peroxide which powered the pumps and generators. The aircraft reached 0.79 Mach (522 mph) during the 4 minute, 56.6 second flight.

In his autobiography, Always Another Dawn: The Story of a Rocket Test Pilot, by Crossfield and Clay Blair, Jr., Crossfield described the first flight:

“Three” — “Two”— “One”

“DROP”

“Inside the streamlined pylon, a hydraulic ram disengaged the three heavy shackles from the upper fuselage of the X-15. They were so arranged that all released simultaneously, and if one failed, they all failed. The impact of the release was clearly audible in the X-15 cockpit. I heard a loud ‘kerchunk.’

“The X-15 hung in its familiar place beneath the pylon for a split second. Then the nose dipped sharply down and to the right more rapidly than I had anticipated. The B-52, so long my constant companion, was gone. The X-15 and I were alone in the air and flying 500 miles an hour. In less than five minutes I would be on the ground.

“There was much to do in the first hundred seconds of flight. First I had to get the feel of the airplane, to make certain it was trimmed out for landing just as any pilot trims an airplane after take-off or when dwindling fuel shifts the center of gravity. Then I had to pull the nose up, with and without flaps, to feel out the stall characteristics, so that I would know how she might behave at touchdown speeds. My altimeter unwound dizzily: from 24,000 to 13,000 feet in less than forty seconds.

“The desert was coming up fast. At 600 feet altitude I flared out. . . .

“In the next second without warning the nose of the X-15 pitched up sharply. It was a maneuver that had not been predicted by the computers, an uncharted area which the X-15 was designed to explore. I was frankly caught off guard. Quickly I applied corrective elevator control.

“The nose went down sharply. But instead of leveling out, it tucked down. I applied reverse control. The nose came up but much too far. Now the nose was rising and falling like a skiff in a heavy sea. Although I was putting in maximum control, I could not subdue the motions. The X-15 was porpoising wildly, sinking toward the desert at 200 miles an hour. I would have to land at the bottom of an oscillation, timed perfectly; otherwise, I knew, I would break the bird. I lowered the flaps and the gear.

“With the next dip I had one last chance and flared again to ease the descent. At that moment the rear skids caught on the desert floor and the nose slammed over, cushioned by the nose wheel. The X-15 skidded 5,000 feet across the lake, throwing up an enormous rooster tail of dust.”

June 8, 1966: June 8, 1966: XB-70A Valkyrie Number Two was flying in close formation with four other aircraft — an F-4 Phantom, an F-5, a T-38 Talon and an F-104 Starfighter. During the flight, the F-104 drifted into the XB-70s right wing, flipped and rolled inverted over the top of the Valkyrie, destroying the bomberís vertical stabilizers. The F-104 then exploded, destroying the Valkyrieís rudders and damaging its left wing. With the loss of both rudders and damage to the wings, the Valkyrie entered an uncontrollable spin and crashed north of Barstow, Calif. NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker (F-104 pilot) and Carl Cross (XB-70 co-pilot) were killed. Al White (XB-70 pilot) ejected, sustaining serious injuries. Following an investigation into the incident, the XB-70 program returned to flight Nov. 3, 1966.

For more, visit https://www.aerotechnews.com/blog/2020/06/12/high-desert-hangar-stories-the-loss-of-the-xb-70-valkyrie-seconds-that-last-forever/

June 8, 1967: Israeli planes and one or more torpedo boats mistakenly attacked the U.S. Navy research ship, the USS Liberty, in the Mediterranean Sea near the Sinai Peninsula.

June 8, 1988: At Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., the X-29 Advanced Technology Demonstrator Aircraft flew its 200th flight, becoming the first X-plane ever to reach that number.

June 8, 1998: Space Shuttle Discovery undocked from Russian Space Station Mir and pulled away, signaling an end to the first phase of co-operation between the U.S. and Russia. The second phase of the experiment involved the construction of the International Space Station.

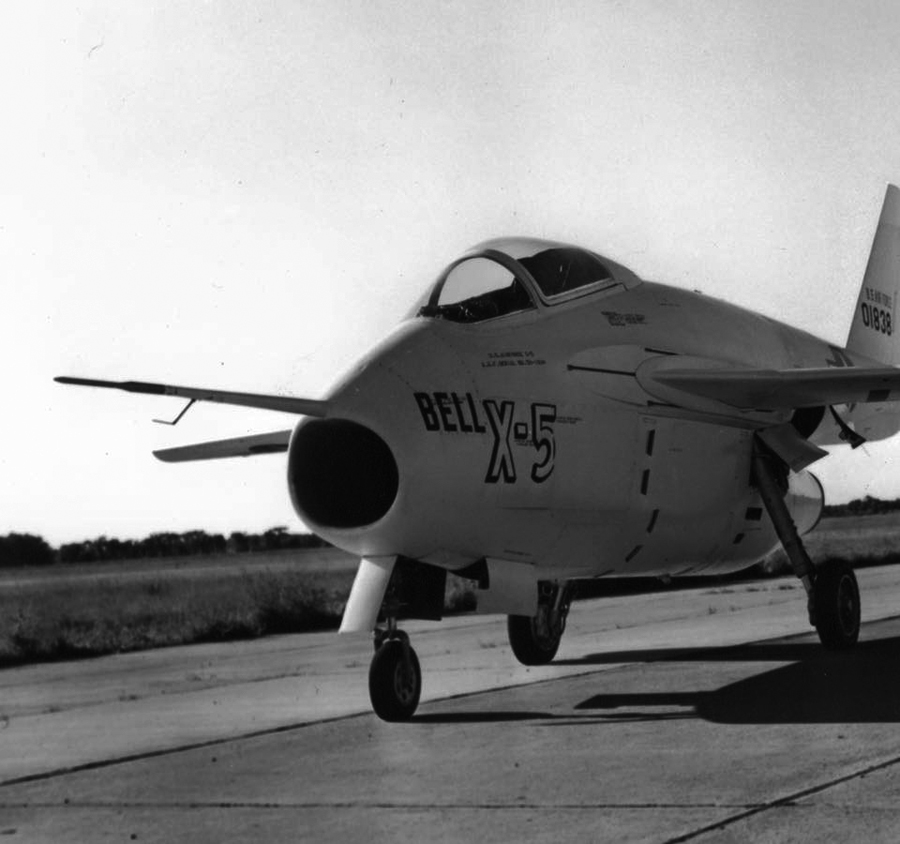

June 9, 1951: The first X-5 variable-sweep wing jet research aircraft arrived at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., from Bell Aircraft Corporation. This was a NACA project to determine the usefulness of a variable-geometry wing.

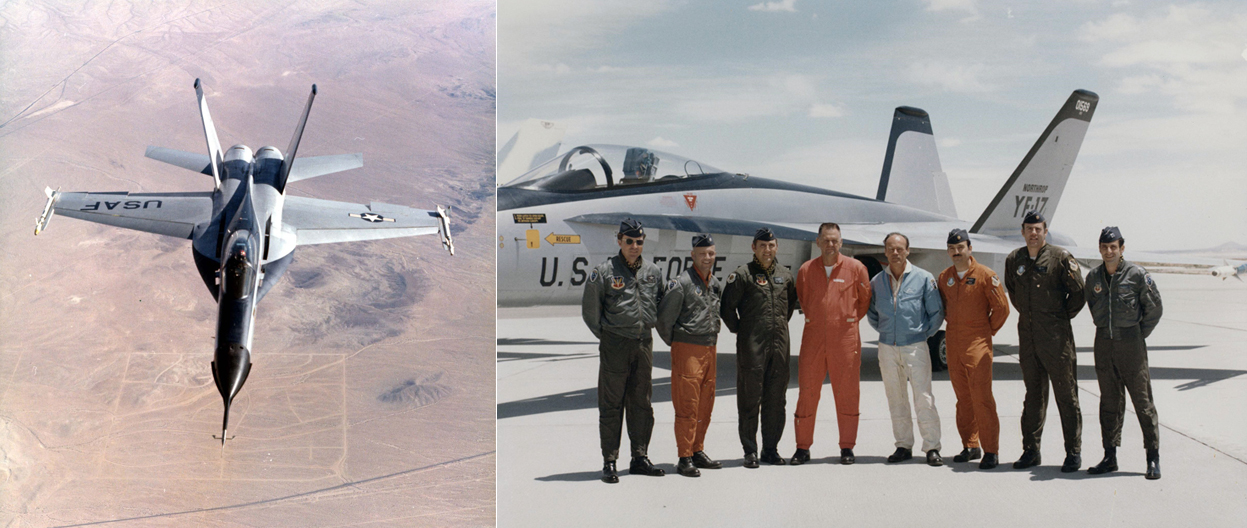

June 9, 1974: The Northrop YF-17 Cobra, with Henry “Hank” Chouteau at the controls, made its first flight at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Following the flight, Chouteau remarked that, “When our designers said that in the YF-17 they were going to give the airplane back to the pilot, they meant it. It’s a fighter pilot’s fighter.”

Through 1974, the YF-17 competed against the General Dynamics YF-16 as part of the U.S. Air Force’s Lightweight Fighter technology evaluation program. The two YF-17 prototypes flew 288 test flights, totaling 345.5 hours. The LWF was initiated because many in the fighter community believed that aircraft like the F-15 Eagle were too large and expensive for many combat roles.

Although it lost the LWF competition to the F-16 Fighting Falcon, the YF-17 was selected for the new Naval Fighter Attack Experimental program. Initially, the U.S. Navy was not heavily involved as a participant in the LWF program. In August 1974, Congress directed the Navy to make maximum use of the technology and hardware of the LWF for its new lightweight strike fighter, the VFAX. As neither contractor had experience with naval fighters, they sought partners to provide that expertise. General Dynamics teamed with Vought for the Vought Model 1600; Northrop with McDonnell Douglas for the F-18. Each submitted revised designs in line with the Navy needs for a long-range radar and multirole capabilities.

In enlarged form, the F/A-18 Hornet was adopted by the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps to replace the A-7 Corsair II and F-4 Phantom II, complementing the more expensive F-14 Tomcat. This design, conceived as a small and lightweight fighter, was scaled up to the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, which is similar in size to the original F-15.

Aerotech News and Review, published every other Friday, serves the aerospace and defense industry of Southern California, Nevada and Arizona.

News and ad copy deadline is noon on the Tuesday prior to publication. The publisher assumes no responsibility for error in ads other than space used.

The appearance of advertising in this publication, including inserts or supplements, does not constitute endorsement by the Department of Defense, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, or Aerotech News and Review, Inc., of the products or services advertised.